(Chess News) R Praggnanandhaa’s remarkable journey at the FIDE World Cup in Baku came to a close on Thursday, as the reigning World No. 1, Magnus Carlsen, secured victory with a 1.5-0.5 score in the tiebreaker, ultimately claiming the chess championship.

Following a draw in the initial two games played in the traditional format, Carlsen managed to clinch triumph against Pragg on Thursday by winning just two games under the shorter time control of 25 minutes during the tiebreaker.

Pragg, who marked his 18th birthday during the course of the World Cup, has etched his name as the youngest finalist in history. Emerging from Chennai, this young talent, seeded 31st, has now additionally secured the distinction of being the lowest-seeded contender to ever reach the final stage.

Prior to taking Carlsen to the tiebreaker, Pragg had eliminated the campaigns of Hikaru Nakamura, ranked World No. 2, and Fabiano Caruana, ranked World No. 3. He has now solidified his position in the eight-player Candidates Tournament (an event conducted to identify a contender for the current world champion).

Nurtured within the influence of his sister, Vaishali Rameshbabu, a celebrated local chess champion, Pragg embarked on his chess journey at the tender age of three. Demonstrating remarkable abilities from a very early stage, he earned the title of the world’s youngest International Master in 2016, achieving this feat at the age of just 10. His ascent continued, securing the title of Grandmaster at the age of 12 in 2018, making him the second youngest player to attain such status back then. Impressively, he also reached the 2600 ELO rating milestone by the age of 14, setting yet another world record at that time.

Nonetheless, on Thursday, the World Cup championship remained beyond his grasp. Carlsen’s wealth of experience proved to be the decisive factor. In the initial tiebreaker, Carlsen triumphed in a 47-move game even while playing with the black pieces. A mere day prior, employing white, Carlsen had strategically aimed for a draw during the second classical match—an approach that Viswanathan Anand, a five-time World Champion, likened to Carlsen’s tactics seen in the 12th match of the 2016 World Championship encounter against Sergey Karjakin.

Any potential residual effects from the food poisoning he had experienced after his semi-final victory over Nijat Abasov didn’t appear to manifest in Carlsen’s performance on Thursday. He remained composed and unyielding as he faced Pragg, astutely noting that the young player was struggling with time constraints during the initial tiebreaker. Carlsen responded by injecting complexity into the game and simultaneously accelerating his pace, akin to a driver with the urgency of an ambulance. He executed moves with rapidity toward the end, leaving Pragg with minimal room to contemplate a stronger defense. Carlsen persisted until Pragg ultimately conceded. In the subsequent match, Carlsen secured a draw to secure his triumph.

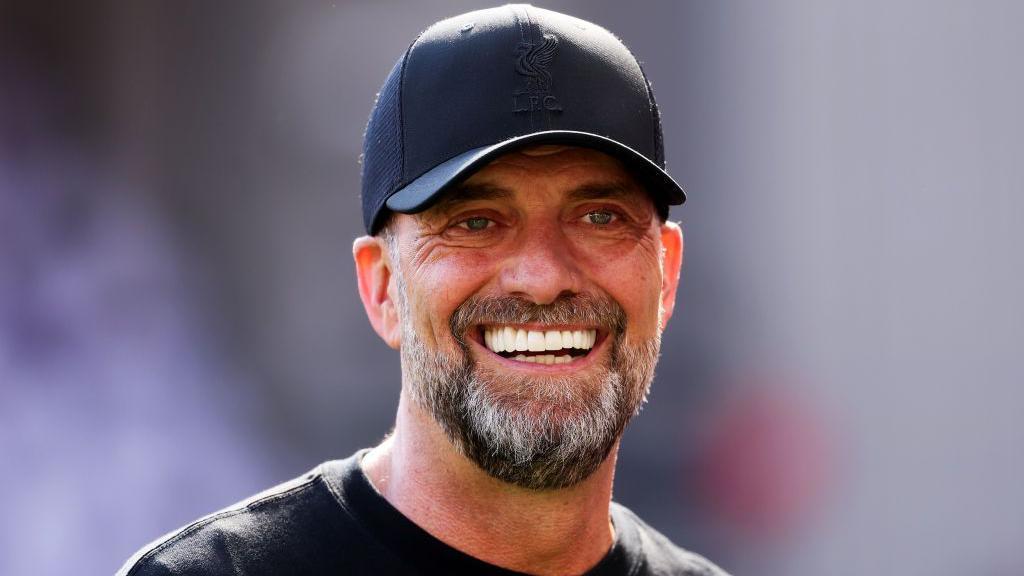

Preceding Thursday, the Norwegian had already established an impressive portfolio: a five-time classical world champion, a four-time rapid world champion, a six-time world blitz champion, and the World No. 1 since 2011. Nevertheless, the World Cup title had remained absent from this list. Immediately following his victory over Pragg on Thursday, Carlsen shared a tweet accompanied by a GIF, asserting that he had “conquered chess.”

This achievement arrives at a pivotal juncture in Carlsen’s career. Earlier in the year, he chose not to defend his position as the world champion, thereby relinquishing his right. Consequently, the 32-year-old was succeeded by Ding Liren, marking the first time since 2013 that Carlsen had not held that title.

Carlsen’s reasons for his decision were quite straightforward: a lack of motivation and a desire to avoid the demanding nature of another campaign.

On Thursday, Chess24 asked Carlsen if his World Cup victory had altered his perspective on classical chess. He replied, “I wouldn’t say it increases the chances that I will play this again. Winning the World Cup wasn’t really a goal for me before 2017. After my poor performance, I felt that I couldn’t allow this to define my legacy in the World Cup.”

He indicated that he participated in the World Cup to make a statement. “If my results in classical chess clearly showed that I am still the dominant player in the world, I wouldn’t have participated here,” he explained.

“From nearly the beginning of the World Cup, I’ve been questioning myself, asking why I am dedicating so much time to classical chess, which I find both stressful and monotonous. It’s not a favorable state of mind,” Carlsen shared on FIDE’s YouTube channel in a previous interview.

The defeat to Vincent Keymer acted as a wake-up call. In 2017, Carlsen had faced an early exit when he was defeated by World No. 35 Bu Xiangzhi in the third round. He commented, “My thoughts were, if I lose and get eliminated, it would be another humiliation in the World Cup. I know I’ll move on from it in a couple of days, but it’s still less than ideal. Now, I’ve had my first serious scare.”

That unsettling experience appeared to ignite Carlsen’s interest in classical chess. During the round of 16 match against Vasyl Ivanchuk, Carlsen declined a draw proposal from his Ukrainian adversary in the second game, even though victory wasn’t necessary since he had already won the first game.

In the semi-final against Nijat Abasov, Carlsen arrived early and created a widely shared moment by extending his hand toward an unoccupied chair across the board. He initiated the opponent’s clock, even as Abasov arrived a few seconds late, and then patiently waited. Reflecting on the incident, Carlsen stated, “It was meant as a jest.” As it transpires, his commitment to victory was absolutely unwavering.

Also Read: As Praggnanandhaa and Gukesh shine, is India the new talent-churning machine in chess?